Editors note: One takeaway shared by many COP fellows was the power that a single story can hold. It’s easy to become overwhelmed or numb when looking at climate change and environmental degradation from the global perspective. Listening to another’s story and empathizing with them is vital to finding solutions to the problems we face. Below are four blogs from some of our COP fellows that discuss this idea. This is the first in a series of blogs that will be posted in response to UConn@COP24.

Communicating Climate Change – Delaney Meyer

The Talanoa Dialogue is Making People Care! – Kat Konon

The Emotional, Psychological, and Mental Impacts of Climate Change – LeAnn McLaren

Personal Connections: Making Climate Change Hit Home – Luke Anderson

The Media’s Role in Communicating Climate Science – Delaney Meyer

Providing Platforms to Broaden Perspective – Luke Anderson

Communicating Climate Change

By Delaney Meyer – Junior, B.S. Civil Engineering

During one of our morning discussions while attending COP24, we analyzed the Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator. This indicator is determined through a series of questions, which are designed to determine a preference between four comparisons. The comparisons include; extroversion versus introversion, sensing versus intuition, thinking versus feeling and judging versus perceiving. Each of the student fellows in the UConn@COP24 group used the indicator in order to determine where they would fall when compared to other groups of people. Based on data provided by UConn@COP faculty member, Scott Stephenson, the results of the group members’ distribution for indicator codes proved to be similar to results nationwide. Examining the data, the most glaring difference when comparing these two groups was based on the sensing versus intuition comparison. Nationwide the ratio was 73% to 27% while the fellows’ ratio was 31% to 69% respectively.

As a group, we dove into possible reasoning behind this difference and analyzed how this indicator could be used to improve the portrayal of climate change information. As students, we naturally prefer intuition to sensing. This is because of our curiosity and desire for explanations to problems. We do not accept our reality for what it is, we want to understand why it is the way it is and in the context of climate change, fix it. Thus, we can take statistics given to us and apply them to our reality.

Nationwide, people fall on the opposite side of the spectrum and seem to simply focus on their current reality and accept it for what it is. In this context, statistics cannot provide these people with an accurate depiction of what reality is like for others. In order to change this, climate change effects will have to become more personal to those all over the world. During our discussion, we asked ourselves how this could be done and turned to our experiences at COP24 for guidance.

One way in which effects of climate change have effectively been portrayed at COP24 has been through storytelling. Through a story, people are able to convey experiences and emotions to others. When listening to a story it is easy to put yourself into the story teller’s shoes and experience their reality as your own, which would be beneficial to those who focus on their present reality.

The stories that I have experienced while at COP24 have triggered a range of emotions. I experienced a woman firefighter from Greenpeace speak about how wildfires have impacted her. She spoke of her home in Indonesia and a wildfire, which destroyed much of the land that she knew as her home. She broke down in tears while telling this story showing vulnerability and causing many of us in the audience to begin to cry. Through this experience, I was able to better understand the impact of wildfires on communities. I was also able to connect with this woman through the feeling of intense loss that she had allowed us to experience with her. We were able to experience stories such as this one repeatedly throughout our week at COP24.

COP24 taught our group how to better convey information about climate change to the public. Through the use of storytelling as a technique to portray the impacts of climate change to the general public, we believe that people will develop a better understanding of the reality that others are facing due to climate change.

The Talanoa Dialogue is Making People Care!

By Kat Konon – Junior, B.S. Chemical Engineering

Most people, especially in light of the most recent IPCC report, know something about climate change. Some people focus on the science behind it, others focus on the consequences, and still others decide to ignore it altogether. It can be hard to process all the warnings, statistics, and charts that we learn about in school or see on the news. Because of this, Fiji introduced the Talanoa dialogue at COP23, which aims to give people a platform to “share stories, build empathy and to make wise decisions for the collective good.” This concept carried over into COP24.

I attended many different talks covering topics such as policy, renewable energy, plant-based diets, and youth action, but the ones I continue to think about the most were people from around the world simply sharing their stories. One speaker from New Zealand talked about how each year, summers in her community are magical. There’s fresh fruit, beautiful weather, and an overall lightheartedness. However, in recent years, summertime has also brought overtones of anxiety and fear as wildfires, a product of extreme record-breaking drought, grow more and more destructive. If that isn’t bad enough, her low-lying community’s land will be underwater by the end of her lifetime. As she talked she emanated sadness and frustration, but her drive to prevent others from having the same fate spoke the loudest. She called for climate justice and climate equity, phrases I heard over and over at the conference. Together, these ideas convey that global warming is an ethical and political issue, and it generally poses the greatest threat to those who are the least responsible. Therefore, developed countries need to provide aid to those in less developed countries who are disproportionately impacted by climate change.

Another speaker from China talked about how 10 years ago, when she was a child, she could see the stars. Now, she looks up and they’re not there because of pollution. If you can’t imagine wildfires or floods destroying your home, try to imagine this. It just makes me feel so sad.

There are a ton of reasons to care about climate change. So many, in fact, that it can be overwhelming. So start here. Start with the people who have to face it every day. Show some empathy and do your part to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. You’d hate to be in their shoes someday.

The Emotional, Psychological, and Mental Impacts of Climate Change

By Leann McLaren – Senior, B.S. Political Science and History

During my time as a member of the UConn@COP24 cohort attending the United Nations’ Conference on Climate Change in Poland, I had the opportunity to participate in an event titled “Intergenerational Inquiry: Youth Stepping Up for Climate Action.” The event showcased multiple speakers from the UN Secretary General for Youth to delegates from Ghana and students from many different countries.

What I found especially provoking was the testimony from a youth activist from the island of Jamaica. He described his struggle of being exiled from his community as a kid due to his LGBTQ identity. From his story of homelessness he described how the impacts of climate change took an emotional toll on him in addition to his family problems. In Jamaica, he described how as a developing island nation, much of the national disasters have the ability to wipe out entire nations of people. The harsh effects of climate change disproportionately affected people who were not primary contributors of GHG emissions.

Similarly, with another student from India, he described how his motivation to become an activist for climate justice stemmed from his childhood. Memories of morning runs with his father in India became progressively dangerous as temperatures increased to over 125º degrees Fahrenheit. The harsh effects of climate change affected not only his health but also his emotional connections with his father. He explains how these changes impacted his psychological development and contributed towards his activism.

Overall, the students and speakers in this event resonated with me. The narrative of their personal stories allowed me to see how climate change produced much more than physical effects, but negative emotional and mental health side effects as well. This event made me more aware of the totality of impacts caused by climate change and more motivated to take action as a result of these realizations. I now aim to reduce my personal emissions and raise awareness to promote behavioral change among others, not only for the sake of preventing the catastrophic increase in global temperatures, but also for the mental, emotional, and psychological well-being of others all over the world.

Personal Connections: Making Climate Change Hit Home

By Luke Anderson – Junior, B.S. Nutritional Sciences and Anthropology

Emotionally, UConn@COP24 was a very impactful experience. We began our first full day in Poland with a tour of the concentration camps from World War II, Auschwitz I and Auschwitz-Birkenau. This set the tone for the sort of raw emotional vulnerability that made my personal experience at COP transformative.

I’ve heard many stories about others’ sobering experiences visiting Auschwitz, but to approach our guided tour through the lens of climate justice made the history of dehumanization and devastation surrounding the Holocaust surprisingly more relevant to the circumstances of the world today. I saw this in climate-induced refugee displacement of those in the developing world and the intersectionality of the people who are so heavily affected by xenophobia and other forms of hatred and the universal impacts of climate change.

This is where I drew connections to my own life and where this trip really helped me rekindle my passion to push for change.

I was able to connect with people through their stories. Pictured to the right is Laura. She is a volunteer firefighter with GreenPeace from Indonesia who very emotionally shared the story of how her village has become devastated by the haze of wildfires, which both exacerbate and are exacerbated by atmospheric carbon emissions. She’s among the many worldwide whose lives have been threatened by diagnoses of upper respiratory and cardiovascular infections and chronic diseases as a result of these conditions. As she shared about the loss of friends who she’s lost to fires and the health effects wildfires have had in Indonesia she began to cry and was comforted by other volunteer GreenPeace firefighters from other areas of the world.

Throughout my childhood I had always considered myself well-off and disconnected these sort of impacts of climate change and how they disproportionately affect people of poorer communities. However, when I suddenly lost my father to a heart attack last year I was forced to face how rapidly public health crises, such as those caused by climate around the world, can impact any of us and how we have to interact with the world. My mother hasn’t worked a full-time job since I was born and after my father’s death, we became dependent, in many ways, on his life insurance and the healthcare benefits we were fortunate to still be able to receive through his employer. Hearing Laura’s story and stories like hers made me viscerally acknowledge how common stories like mine are and will continue to become. With the acceleration of climate change, this will happen first among minority populations and those in the developing world, then for the rest of us whose lack of exposure allows us to remain inactive in fighting for climate action and justice.

The Media’s Role in Communicating Climate Science

By Delaney Meyer – Junior, B.S. Civil Engineering

Having had a little over a week to reflect on my experience while in Poland for COP24, I am overcome with the abundance of information that I was presented with. However, I am stuck thinking about one particular experience that I had while at the climate hub. From this particular experience, I was able to gain important statistical knowledge and further understand how the media can spread messages about climate change more effectively.

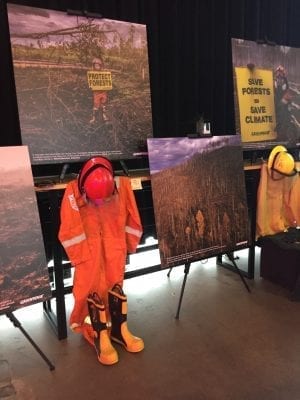

The second day that I attended the climate hub, Greenpeace had several sessions about wildfires planned for the day. When we first walked in, there were visuals of firefighters and wildfires set up in addition to fire fighting gear on display as can be seen in the pictures attached. These images had an immediate impact on me and put the intensity of these fires into perspective. I sat down with a few other students to listen to one of the Greenpeace firefighters discuss his job as a volunteer and introduce another woman to discuss the impacts of wildfires on climate change.

It was emphasized continually throughout the presentations that we witnessed that fires are a contributor to climate change and are a part of a continuous positive feedback loop. This feedback loop consists of an increase in temperatures leading to drier conditions that are prone to fires. The fires release huge amounts of carbon and methane into the atmosphere, which are both potent greenhouse gases. This release of gas leads to worsening global warming. This loop is continuous and becomes worse and worse as time goes on.

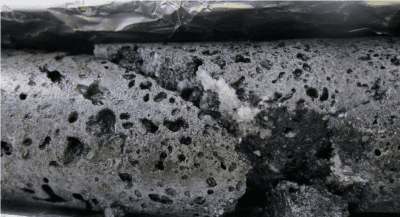

Although warming temperatures are a large reason that many of these fires have the fuel to begin, humans are also making this worse through the use of palm oil. Many peatlands, which are naturally wet and would be highly unlikely to catch on fire, are drained and burned in order to produce palm oil. Palm oil can be found in the majority of products that people use on a day-to-day basis including cosmetics, detergents and many different foods. It can be difficult to determine whether palm oil is present in many products because there are dozens of different terms that can be used to describe palm oil in a list of ingredients. The use of palm oil does not need to be stopped completely, however it is important that the general public becomes aware of the impacts that unsustainably produced palm oil has. When shopping it is important to look for the RSPO label and the Green Palm Oil label, which both ensure that the palm oil for that product has been sustainably produced.

After we had been given all of the facts about how fires can have such a large impact on climate change, another volunteer firefighter from Indonesia took the stage to share her story. She explained that the draining of peatlands near her home lead to a large fire which destroyed much of her community and killed many of her close friends. As she shared her story, she had to pause to compose herself, which portrayed just how much of an impact these fires had on her life. By the end of the story, much of the audience was in tears along with this woman and had a deeper understanding of how a small choice of what product to eat or use can impact someone’s life across the world.

This experience emphasized how important story telling is when attempting to make a point. This was a theme that many of us saw throughout the COP and feel should be used in order to effectively portray climate change to people across the world. Testimonials evoke an emotional response out of people, which they are more likely to act on than when exposed to a bunch of statistics and political discussions. When educating others about climate change we need to appeal to people’s emotions to spark motivation for change.

Providing Platforms to Broaden Perspectives

By Luke Anderson – Junior, B.S. Nutritional Sciences and Anthropology

Despite having a long way to go in terms of whose interests are served and what actions are taken, COP is a place where people from all backgrounds can have a platform for their voices to be heard and to get involved in combating climate change. One of the reasons for this is because environmental issues, and climate change in particular, impact every aspect of each of our lives.

Climate issues require remarkably interdisciplinary solutions. As someone who is frequently asked about how my studies in Anthropology, Nutritional Sciences, and Mathematics are connected to climate change, attending COP24 really appealed to me as an opportunity to explore these connections.

And COP24 did not disappoint. Because of the interdisciplinary and multi-cultural nature of the COP, I was constantly surrounded by people whose lives encompass vastly different experiences from my own. I was empowered by the incredible enthusiasm of the people I met for getting young people involved in their work to combat climate change and minimize its exponential impact on future generations.

The picture [to the right] is from a panel discussion, which was followed by audience (and UConn student) participation, about the role of intergenerational engagement in the Talanoa Dialogues, a COP platform focused on humanizing the effects of climate change and informing policy making through storytelling. At the event we were able to connect with other students, policy advisors, activists, and people involved in the United Nations Human Rights Council, among others.

Fellow UConn@COP delegate Emily Kaufman and I were invited to this event by Jean Paul Brice Affana (second from right), a policy advisor on climate finance and development from Bonn, Germany, after a moving panel the previous day. We came to this panel dispassionate and drained from the lack of meaningful personal connections we had been able to make exploring the COP venue that morning. The panel featured Jean Paul, director of the documentary on youth activism in the climate movement “Youth Unstoppable” Slater Jewell-Kemker (front left), Fijian Minister Inia Seruiratu who was instrumental in helping establish the Talanoa Dialogue at COP23, and 15-year-old activist and global climate strike leader Greta Thunberg. After a passionate and blunt address on the reality of climate change from Greta and an emotionally impactful screening of the trailer for Slater’s film, Emily and I approached Slater and Jean Paul in tears thankful for the stories shared on the importance of passionate young people in the climate movement.

In political dialogue, in the United States and elsewhere, we see a lot of apathy, especially around issues as vast and daunting as climate change. However, this apathy, and a lot of our inability to act on pressing issues, is rooted in a lack of connection and subsequent inability to empathize with the stories of those who are most affected. Platforms for sharing stories such as documentaries, sitting down with a traveler from Norway in the Kraków market over some kielbasa and mulled wine, or formalized panels under the Talanoa Dialogue help to bridge these gaps and broaden perspectives to a point where most people come to realize that, regardless of cultural barriers, all over the world we are fundamentally the same. Without these platforms it’s too easy to lose sight of the values and life experiences that bind us.

In the words of chef Anthony Bourdain on his career traveling the world connecting people through their stories, “If I’m an advocate for anything, it’s to move. As far as you can, as much as you can. Across the ocean, or simply across the river. Walk in someone else’s shoes or at least eat their food. It’s a plus for everybody.”

I wholeheartedly believe that the world would be better off if our ambitions were more firmly grounded in our values than our résumés. And traveling with UConn@COP across the ocean has helped cement that sentiment.

COP24 yielded immense frustration with the status of global climate action. The current course of climate change mitigation, if continued, is on pace to put the 2 degree Celsius warming goal from Paris out of reach by 2030. The United States conducted a side event promoting coal and other fossil fuels and also partnered with Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait to blunt the acceptance of the alarming new IPCC report, detailing action required to prevent 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, coordinator of the Association of Native Peul Women of Chad, pleaded for climate action on behalf of her people’s lives, but was given few tangible results. The host venue offered a meat-laden dining menu and lined its walls with plastic cups and jugs of water, juxtaposing the purpose of the conference with blatantly unsustainable practices.

COP24 yielded immense frustration with the status of global climate action. The current course of climate change mitigation, if continued, is on pace to put the 2 degree Celsius warming goal from Paris out of reach by 2030. The United States conducted a side event promoting coal and other fossil fuels and also partnered with Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait to blunt the acceptance of the alarming new IPCC report, detailing action required to prevent 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, coordinator of the Association of Native Peul Women of Chad, pleaded for climate action on behalf of her people’s lives, but was given few tangible results. The host venue offered a meat-laden dining menu and lined its walls with plastic cups and jugs of water, juxtaposing the purpose of the conference with blatantly unsustainable practices.

Environmental justice, put simply, is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to environmental conditions, regulation, and change. Those on the frontlines of climate change and other forms of environmental degradation are often the most economically and politically repressed. Impoverished island nations facing increased hurricane activity, poor urban communities facing the worst of air pollution, minority communities having little influence over the siting of a landfill in their backyard, and indigenous people facing potential contamination of their rivers by powerful oil companies should be given a seat at the table in discussions of policy and change. After all, they’re the ones who have experience dealing with the problems that we’re trying to solve.

Environmental justice, put simply, is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to environmental conditions, regulation, and change. Those on the frontlines of climate change and other forms of environmental degradation are often the most economically and politically repressed. Impoverished island nations facing increased hurricane activity, poor urban communities facing the worst of air pollution, minority communities having little influence over the siting of a landfill in their backyard, and indigenous people facing potential contamination of their rivers by powerful oil companies should be given a seat at the table in discussions of policy and change. After all, they’re the ones who have experience dealing with the problems that we’re trying to solve.